Welcome to the era of sex negativity

Depictions of sex are everywhere, but no-one is having fun.

Sex is hyper-present in much public and pop culture discourse – but it’s not really sexy, it’s actually…kind of bleak.

There are, of course, some recent, much-discussed films that attest to this. You already know them, but let’s pretend you don’t.

First up, the Halina Reijn film Baby Girl, which sees Romy, a female CEO, engage in power play with an intern. In the film’s emotional climax, she confesses it all to her husband and explains, in tears, that she feels like there’s something wrong with her due to her predilection for S/M porn and the fact she gets off on risky sex. It seems as if the film luxuriates in her shame, on the negative ripples her sexual agency causes in her family, before folding her back into the heteronormative family unity without any real release or resolution to her feelings.

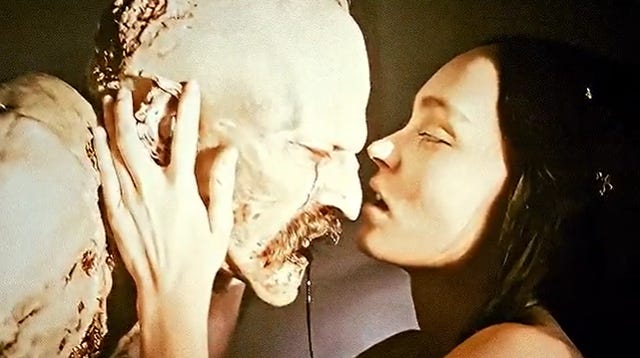

Nosferatu, the good ol’ vampire psycho-sexual drama and Dracula reboot, also presents us with another spectacle of feminine sexual shame. Ellen’s attraction to Count Orlok – who represents a kinky, high-risk sexuality that contrasts with the sexual containment of the marriage unit – is cast as a hideous contamination, a social rot, and her succumbence to this desire is an act of self-destruction. Interestingly, it’s only by surrendering to her own debasement that she can save her wider community.

In both of these films, female desire – at least when embodied by a white, idealised woman – is seen as corruptive force, a process of auto-abjection which threatens a woman’s identity, knocks her off of a pedestal of presumed innocence, and undermines the safety of the world around her.

These works are doing nothing transgressive when it comes to depictions of heterosexual, female desire. In fact, I would say that they are remarkably conservative – rather than granting their female protagonists agency or the possibility of living vibrant, fulfilled sex lives, they must choose between the facile domestication of desire or complete annihilation. The fact that these films resonated so much with the public is a grim indictment of just how regressive and unimaginative our sexual imaginations have become.

While sexual empowerment and rewriting the sexual script around gender was once the goal of much pop feminism, the tables have turned. Now, many young women are embracing sex negative politics.

In the wider world, there has been the resurgence of phenomena like 4B (political celibacy that sees straight women basically go on sex strike) and lavender marriages (sexless marriages of convenience between LGBTQIA+ people of incompatible sexualities).

In the media, young celebrities are offering reductive, sweeping condemnations of porn. In recent years, Billie Eilish has said that early exposure to porn ‘destroyed’ her brain. More recently, nepo du jour Gracie Abrams shared the following: “Porn is bullshit. It is dangerous, not real, and a performance.” (Naturally, it seems lost on her that porn is performance, porn performers are part of the entertainment industry – like her – and deserve solidarity).

I have seen precisely one article noting that the works of Andrea Dworkin have been taking off among Gen Z – someone who railed against the porn industry and whose provocative works posited that all heterosexual sex is degrading and coercive. But I would say that her influence, and her profound pessimism about heterosexuality and sex, has a much broader impact than we can account for.

Dworkin was part of a wider, anti-porn, anti-BDSM, anti-sex work and anti-sex strain of feminist thought that we can classify as ‘sex negative’. While young women might not know the origin point, they’ve definitely been swept up in this line of thought.

Other thinkers in this vein include Catherine MacKinnon – a feminist legal scholar who collaborated with Dworkin on attempts to overhaul the legal framework around porn. Specifically, MacKinnon wasn’t a fan of policing porn by using obscenity law and instead argued that porn generated the social subjugation of women – an argument that many still repeat to this day.

It’s not hard to understand the misguided appeal of this kind of rhetoric. Squaring the never-ending content mill of feminist lite messaging with the persistence of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and the eradication of state support for the most vulnerable women, has young women reaching out for politics which affirms their experience. Cue: the reemergence of gender discourse which underscores, to the point of reifying, women’s subjugation and which points to porn as an easy scapegoat for sexualised gender inequality.

But it’s hard not to feel like sex negative arguments stall, rather than accelerate progress. Rather than being utopic, progressive or liberatory, they enshrine the status quo. When we have such a pessimistic view of sex and gender relations, it can become a kind of dogma, one which minimises female agency as well as the potential for other, more egalitarian futures.

This is not to understate the harm that patriarchy does to women, or to dismiss individuals’ lived experiences. But it’s time to broaden our thinking, to rediscover sexuality on our own terms, and to bring back curiosity and experimentation to both the bedroom and our sexual discourse.